Baby, it’s HOT outside! For Calves, Too!

Posted: June 13, 2022 | Written By: Anne Proctor, Ph.D., Form-A-Feed

Temperature Humidity Index (THI) calculates the effects of both temperature and humidity. As we say in Wisconsin on those days when it’s miserable to be outside, “it’s not the heat, it’s the gosh darn humidity!” It takes extra energy to get chores done. Clothes are soaked with perspiration and it’s hard to drink enough water to stay hydrated. An 80-degree day with low humidity feels quite comfortable, but high humidity makes it feel much hotter. The THI helps us predict how the environmental conditions will affect the animal. With the sudden increase in temperature recently, heat abatement strategies are in use in the dairy barns, but what are we doing for the calves?

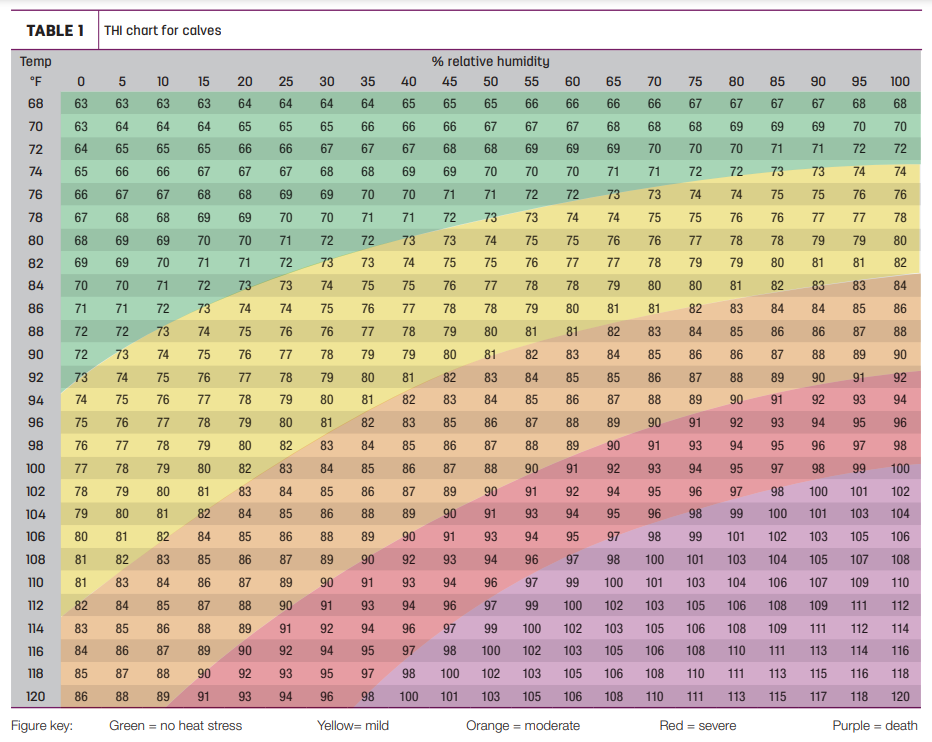

During heat stress, the accumulation of heat from the environment and metabolic processes exceeds the calf’s ability to get rid of heat resulting in an increase in core body temperature. Calves generate less metabolic heat than mature cows and with a higher surface area to volume ratio, a calf can dissipate heat more effectively than a mature cow. While the calculation is the same, the THI at which the calf experiences heat stress is higher for a calf than a cow. The chart below was developed by Zach Janssen from TechMix Global and published in Progressive Dairyman to help farmers and employees determine when to make management changes in response to THI. In the Midwest, our average summer humidity is over 70% and our calves begin to experience the effects of heat stress when the temperature reaches 72-74°F. Our calves are experiencing moderate heat stress at 80 degrees on our lower humidity days and extreme heat stress when temperature is in the low 90s and humidity is high. If you’re hot, your calves are too!

Source: Do calves need a heat stress chart? Zach Janssen for Progressive Dairy Published on 07 May 2021

Let’s consider some strategies to mitigate the effects of high THI on calves and the reasons behind each.

Cool Your Dry Cows

The effects of heat stress on the calf begin before that calf is born if the dam is in a hot environment. Slowed fetal growth during the 60 days before calving and reduced blood flow to the placenta reduces the supply of oxygen and nutrients to the calf results in smaller birthweight calves. Poor colostrum quality because of heat stress effects on the dam combined with the calf’s reduced ability to absorb it can have a negative effect on immunity. Calf raisers can expect a smaller calf that requires more care to manage during periods of heat stress. Start your calf heat stress management plan by focusing your efforts on dry cow housing. Not only will the resulting calf be bigger and better equipped to thrive, but the cow will get a better start to her lactation.

Provide shade and airflow

Mitigating effects of heat stress on both calves and cows begins with the environment. Moving air over the animal improves evaporative cooling. In calf barns, fans and positive pressure systems keep air moving. For calves in hutches, raising the backs off the ground and opening vents will create some airflow. Providing shade will reduce solar radiation whether by using natural shade, installing shade cloth over the hutch pad or simply turning hutches to provide shade in the afternoon will help. Soaking or misting calves is difficult to manage but may be appropriate in some situations. Remember that the water must reach the skin and evaporate to cool the calf which requires both droplets of water and moving air.

Add water

Water intake will naturally increase to counter the loss of body water due to sweating and evaporation from the skin. Providing additional water is essential so the calf can respond to her body’s need for hydration. Calves will drink up to 25% more water during periods of heat stress so we need to be sure we (or employees) are not inadvertently limiting the amount of water available. Fill the buckets and add another trip through the barns daily to refill. An empty water bucket means that we did not allow the calf to consume all the water she needed.

Change your timing

Avoid working calves during the hottest times of the day. Can you wait a day or two to move calves? If you’re always tight on space and see a period of hot weather in the forecast, can you move animals a few days ahead of schedule so that you don’t have to move during the heat stress? At a minimum, shift the timing of tasks to avoid working animals during the hottest parts of the day. It’s not only easier on the calves, but easier on the employees, too. Vaccinating is another task that should be avoided during periods of intense heat stress if possible. We know that immune function is compromised when calves are experiencing heat stress. In addition to the negative effects of handling calves at that time, their bodies may not mount an adequate immune response thereby reducing the effectiveness of the vaccine. Waiting a few days to vaccinate can give you a better return on the investment in product and time.

Get rid of flies

Reduce fly pressure by using a feed-through larvicide in addition to physical methods of control such as spraying, fly tapes/traps or fly predators. Flies create an uncomfortable environment for the calf and the additional standing time wastes energy.

Digestive and metabolic responses to heat stress

Summer calves usually have lower average daily gains than calves born during the cooler months of the year. The combination of higher energy expenditure and lower dry matter intake result in less energy for the calf to use for growth. The modes of action for this effect are well known.

Energy expenditure increases because of increased standing times and processes to remove heat from the body. The heart rate increases during heat stress, and blood flow is redistributed to peripheral tissues to move heat from internal organs to the surface where it can be transferred to the environment. Increased respiration and panting create evaporative cooling but add to the energy demands.

It would be logical to expect a calf with higher energy demands to consume more feed but a heat-stressed calf will eat less. In addition, when feed is digested in the gut, the process produces heat so eating increases core body temperature and results in more heat that the calf must get rid of. VFA production in the rumen is negatively affected by the change in passage rate induced by change in water consumption and lower intakes. With the body shifting blood flow to the extremities to dissipate heat and away from the GI tract, the absorption of nutrients is affected.

The metabolic changes that occur because of heat stress go all the way to the cellular level. Exposure to heat increases the oxidative stress which affects the ability of the cells to meet the additional energy required by the animal. There is a demand for more glucose by the tissues, but that glucose is preferentially used by the central nervous system and immune system. Heat stress interferes with the body’s ability to mobilize adipose tissue resulting in the breakdown of muscle tissue to use protein for energy, further reducing growth. Not only does heat stress impact the amount of energy available for growth, but it uses nutrients already stored in the body to support life during times of heat stress. The result of these and other metabolic changes is lower body weight gain during times of heat stress.

Nutritional management

The higher energy expenditure associated with heat stress combined with the reduced intake that occurs require nutritional strategies to mitigate the loss of ADG. Calves will typically continue to consume all their liquid feed thus the reduction in dry matter intake comes at the expense of the dry feed. As discussed, dry feed creates heat when it is fermented so reducing intake may be a protective mechanism. Increasing the energy density is one strategy to counter the reduced intake and attempt to get more calories into the calf. Shifting fermentation to more propionate and less acetate production by reducing the fiber portion of the ration can reduce the heat of fermentation. Calves need fiber for rumen health so this needs to be a modest reduction in fiber not a full replacement. Fat is energy dense and creates less heat during digestion than carbohydrates or proteins. A rumen protected fat could provide energy with little impact on the already compromised rumen function.

The oxidative stress that occurs because of heat stress results in production of free radicals that damage cells. Providing antioxidants in the diet such as additional vitamins A, C and E and minerals such as zinc can reduce cell damage. Osmolytes are organic compounds that manage the flow of water in and out of cells. During heat stress, osmolytes can be fed to help maintain hydration at the cellular level. Increasing the amounts of sodium and potassium is necessary to replenish electrolytes lost through sweating and maintain the acid-base balance in the blood. These strategies are used by your dairy nutritionists to help mitigate effects of heat stress on lactating cows and are also effective in calves.

Technologies to assist during periods of heat stress

A product for heat stress should contain sodium and potassium (electrolytes), energy sources, a buffer to lower pH, components to help draw/transport water into the cell, osmolytes to maintain cell volume and a flavor/odor that is desirable to the calf. While some of the ingredients are the same, an electrolyte designed for heat stress will be different than one designed for a scouring calf.

There are several products available to help with heat stress and positioning is dependent on the age of the calf. For calves under about two weeks of age when starter intake is limited, the most effective way to get electrolytes, energy, vitamins, minerals and an osmolyte into the calf is through the milk. Products like Bluelite®-C that are labelled to be fed in milk are sure to be consumed and will provide the components desired but will not directly stimulate additional water intake.

For calves that are consuming dry feed, a pelleted supplement such as Hydro-Lac® can be added to the starter or grower mix. Your Form-A-Feed nutritionist can add Hydro-Lac during manufacturing to provide the components needed to address heat stress without compromising the quality of the feed. Some farmers will add Hydro-Lac to the feed as soon as the heat arrives and use it throughout the summer while others prefer to add it on the farm for several days before and during a period of heat stress. Either strategy can work but having it in the feed ensures that the calf is ready whenever the heat strikes.

For calves of all ages, Bluelite-C in the water is a way to encourage water intake and enhance absorption. In addition to the nutrients, these products are formulated to have an attractive odor and taste to encourage water intake. This strategy works well for calves fed individually. Bluelite-C can be added to the water tank and dispensed into calf buckets. In situations where calves share automatic waterers, a dosing system can be used to add it to the water line.

Keep it simple

A strategy for using heat stress abatement products in your calf feeding program follows:

June 1 – Add Hydro-Lac to your calf starter and grower feeds.

Mild heat stress (THI in yellow zone) – Add another trip through the barn to fill water buckets.

Moderate heat stress (THI in orange zone) – Use Bluelite-C in the milk to add electrolytes and energy sources. Continue to monitor water availability.

Severe heat stress (THI in red zone) – Continue using Bluelite-C in the milk and add it to water to encourage more water intake.

Heat stress occurs when the THI is higher than 72oF, and in the Midwest with higher humidity, our calves are experiencing heat stress for much of the summer. Energy expenditure increases as physiological processes attempt to reduce body temperature at the same time as dry matter intake decreases resulting in poor average daily gains through the summer months. Form-A-Feed’s Hydro-Lac can be added to dry feed and Bluelite-C from TechMix can be used in milk or water to help calves of all ages stay hydrated. A combination of management and nutritional strategies can mitigate these effects to keep calves growing.